Home > Worthington > Worthington Tower > memories

|

Memories from the Worthington Tower

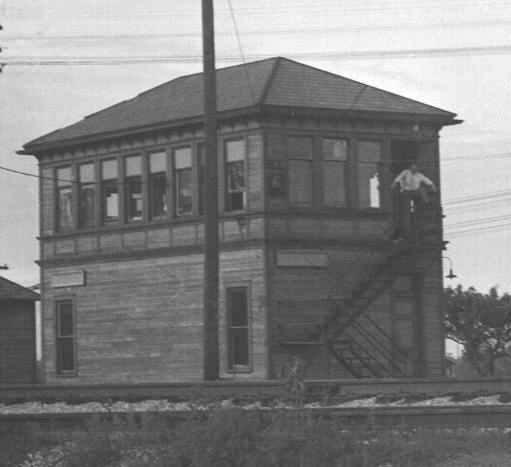

In the 1950’s there was one Worthington tower operator who was welcoming to railfans and would let them visit when he was on duty. His name was Glenn Zigler and he often worked the second trick (3:30pm-10:30pm). Glenn would patiently answer questions and let you know what was going on. Your role was to be good company and keep quiet when things got hectic. Here are a few stories from time with Glenn. Ryan Hoover - Action at Worthington As a boy and adolescent in 1953-1957, I spent many a day at Worthington Tower (WT) just a quarter-mile from my home. WT was indeed a PRR “Armstrong” interlocking plant and its operators were all Pennsy employees. It controlled the crossing of the PRR Sandusky Branch and the Big Four CCC&StL main line. WT also controlled the NYC passing siding just north of the crossing and the PRR crossovers between the double tracks just east and west of the NYC crossing. PRR signals were upper quadrant semaphores also controlled by WT. WT operators routinely stopped Pennsy coal drags to allow NYC passenger and baggage-mail-express trains right-of-way. Pennsy coal trains north to Sandusky and empties south were numerous March-November when Lake Erie wasn’t frozen. There were a few local and general freights but the primary purpose of the branch was to ferry coal from C&O, N&W, L&N (from Cincinnati) and Virginian (via N&W) north to the lakes. I remember a very busy late afternoon at WT once in the summer of 1955. A J1 with an I1 “snapper” (helper) on a mixed road coal drag out of Grogan Yard was stopped at the tower to let an NYC express with a Hudson through the plant northbound, just as a southbound J1 helper eased up to the plant from the north. The PRR semaphores stayed horizontal, though, since a southbound NYC express was waiting in the passing siding. WT gave that train clearance and it proceeded south with an L3 Mohawk. Finally, the operator cleared the northbound drag as the southbound J1 helper headed on across the diamonds tender first. Finally, a few minutes later, a Pennsy H10 on a local freight also clattered over the crossing south toward Columbus. During the summer, WT interlocking could be a very busy place. On occasion, a friendly operator (Glenn Zigler: see introduction above) would let me come up in the tower and even throw a few levers. Those great PRR calendars always hung on the walls and I have yellow “flimsies” (19-order copies) from coal extras headed by J1 6488 and AT&SF Texas 5032 in July 1956. I also saw the X-plorer pass through the interlocking a couple of times. NYC Niagaras were the prized power to catch there. Cliff Clements - Pulling Those Levers As the railroads started their decline after the boom years following World War II, maintenance started to suffer. This was evident in the condition of the track and it also affected maintenance of the infrastructure. Armstrong towers required constant maintenance to keep all the moving parts clear of obstructions and well lubricated. If they weren't properly cared for the operator had a harder time doing his job. If a lever was hard to pull the operator, and especially a young visitor, would put one foot on the lever next to the one being pulled for extra leverage. A two foot lever was really hard to move. To push a stiff lever required putting your whole body into the effort. You could also put your shoulder into the lever and grab the lever next to the one you wanted to move for additional leverage. Cliff Clements remembers one visit when a lever would just not move far enough for the pin to drop. With the Ohio State Limited coming a little creative action was needed so Glenn left Cliff to work the lever while he went down to the track with a crow bar to pry on the stubborn switch. Railroaders were by necessity resourceful people. Alex Campbell - Delivering Coal to the Worthington Tower The tower was heated by a coal furnace located in a small building next to the tower. It was either a hot water or steam system. George Silcott’s Worthington Coal and Supply Co. had the contract to supply coal usually in 5-8 ton loads. The tower was located on the east side of the tracks and the access road, the old CD&M right-of-way, was on the west side of the tracks. To get the coal from the truck to that little building required building a temporary bridge across the tracks with 2X10’s and cement blocks for cribbing. The coal was loaded into a wheel barrow and wheeled across the 2X10’s, behind the tower building, dumped outside the small building and finally shoveled into the building. When George Blake the coal yard’s full time driver and all around fix it man was told he had coal to deliver to the Worthington tower he just rolled his eyes, knowing he was going to work very hard for his money that day. That’s when I got recruited to help him and learned just how hard it can be to push a wheel barrow full of coal across a 2X10 plank without dumping the load on the track. When you are wheeling a loaded wheel barrow you want to spread your feet for stability which we couldn’t do on the 2X10’s. Just about the time we would get in our groove with the bridge built and us wheeling that coal, along would come a train and we would have to take down the bridge and so the afternoon went. George Silcott Gets the Boot One day Glenn arrived at work driving a shiny new red dump truck. He had decided it was time he had a second job driving his own dump truck. It turned out dump truck driving is tiring work and Glenn wasn’t always his old welcoming self. He also took to taking short naps during quiet periods. There was a wide board covering the radiator which was perfect for a 20-minute nap. The tower was equipped with alarms on both the NYC and Pennsy tracks that would sound when a train approached normally giving the operator time to align the switches. One Sunday Glenn must have been extra tired as he didn’t awake until the NYC X-plorer stopped at the tower’s red signal and was blowing its horn for clearance. Unfortunately for George Silcott he picked that time to visit the tower. He asked Glenn, in his cheerful voice knowing full well that Glenn had been caught sleeping, “what happen did you piss in the signal box?” Glenn told him to get out and to not ever comeback. Sometime after Glenn served his two weeks "out-of-service" they made up. |